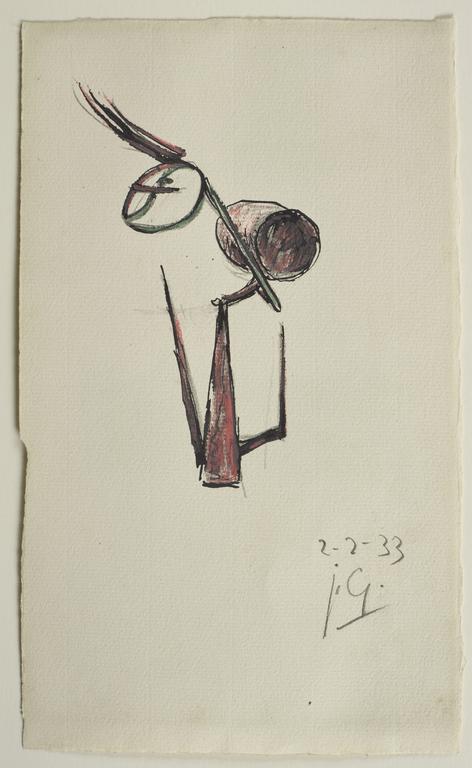

Étude de sculpture

Julio González (1876 Barcelone - 1942 Paris)

1933

Plume et encre de Chine sur crayon de couleur et mine de plomb sur papier vergé ; daté et monogrammé "2-2-33 JG" en bas à droite ; 24,3 x 14,5 cm

Provenance :

Paris, galerie Marwan Hoss ; Berlin, Grisebach, 4 décembre 2020 ; Paris, collection Le Polyptyque ; Paris, collection privée.

Exposition :

Julio González : a retrospective (New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1983, cat. no. 128).

Bibliographie :

J. Gibert, Julio González – dessins – projets pour sculptures figures, Paris, éditions Carmen Martinez, 1975, ill. p. 37.

Ce dessin daté du 2 février 1933, présenté en 1983 dans la magnifique exposition Julio González du Guggenheim Museum à New York, est proche d'un autre dessin, Tête étrange (1932) du Museo Reina Sofia de Madrid. Connu comme Étude pour le Rêve / Le Baiser, une sculpture de 1934 dont l'original en fer forgé se trouve au Centre Pompidou, mais n'ayant pas moins d'affinité avec une autre, Les Amoureux II (1932-1933), il nous semble donc plus adéquat de l'intituler simplement Étude de sculpture.

L'artiste trouve place à la dernière page de l'ouvrage fondamental de Rudolf Wittkower, Qu'est-ce que la sculpture ? :

« Julio González fut un pionnier dans l'usage du fer soudé. Picasso, Calder, (...) beaucoup d'autres suivirent, inaugurant, dans les années 1940 et 1950, un nouvel âge du fer. » Ce raccourci, forcément linéaire, a laissé la place à une vision plus complexe du rôle de González et de son rapport avec Picasso.

Josephine Withers, spécialiste de l'artiste, a montré comment leur collaboration, de 1928 à 1932, a fait de González un véritable artiste, et de Picasso le sculpteur que l'on connaît : créant une œuvre fondée non plus sur le modelage mais l'assemblage, et le plus souvent l'assemblage d'objets « trouvés » – esthétique que l'on retrouve aussi dans ce dessin. Le critique d'art Hilton Kramer a mis en parallèle cette « invention » et celle du cubisme en peinture, le rôle de González et celui de Braque : une forme de discipline et de sensibilité venue pondérer l'instinct du génie qu’était Picasso.

Enfin, la grande historienne de l'art Rosalind Krauss a souligné l'importance du dessin chez González : « un besoin constant de dessiner et souvent, de dessiner d'après nature. » Mais ensuite, le dessin, se faisant sculpture, s'abstrait de la nature. González définit la sculpture, dans un article des Cahiers d'art en 1936, comme « un dessin dans l'espace », un dessin sur une feuille non pas blanche mais vide. Cette liberté nouvelle de la sculpture, son droit au déséquilibre, à la dénaturation, se manifeste avec éclat ici.