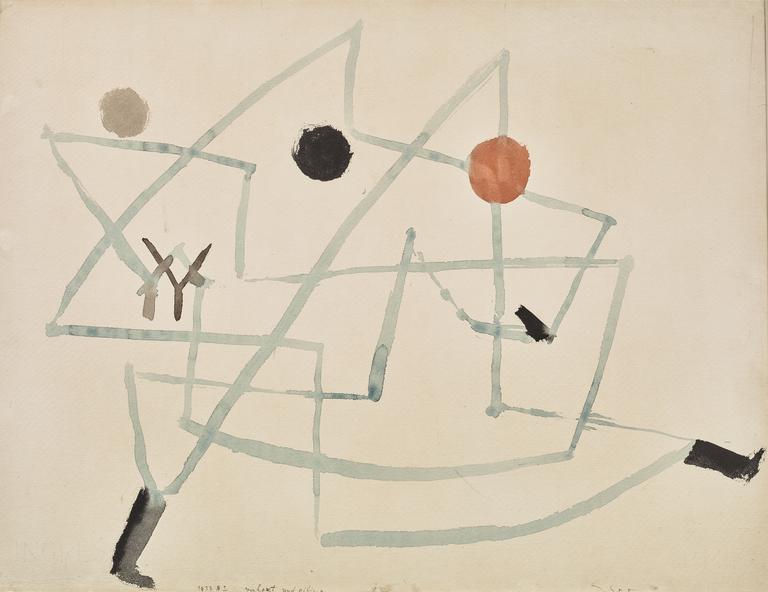

Verhext und eilig

Paul Klee (1879 Münchenbuchsee - 1940 Muralto)

1933

Aquarelle sur papier ; signé « Klee » en bas à gauche, daté, numéroté et titré « 1933 N2 verhext und eilig » en bas au milieu ; 49 x 63 cm

Provenance :

Berne, collection Lily Klee ; Berne, Klee-Gesellschaft (en 1946) ; Paris, galerie Kahnweiler ; Londres, Christie's, 23 octobre 1998 ; Cologne, collection Alfred Neven DuMont ; Cologne, Van Ham, 29 novembre 2017 ; Paris, collection Le Polyptyque ; Stockholm, collection privée.

Exposition :

Paul Klee im Rheinland. Zeichnungen, Aquarelle, Gouache (Bonn, Kunst und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2003).

Bibliographie :

John Sallis, Paul Klee : Philosophical vision : From nature to art, Boston, McMullen Museum of Art, 2012, pp. 165-184 ; Fondation Paul Klee, Catalogue raisonné, vol. VI, Berne, Benteli-Verlag, 2000, n° 6107.

Cette œuvre, son iconographie, sa provenance, résume à elle-seule un moment Klee, qu’on nous pardonne ce jeu de mots. L’Allemagne, où Klee s’était installé en 1898 (avec une parenthèse suisse, son pays d’origine, de 1902 à 1906) bascule après l’accession d’Hitler à la chancellerie fin janvier 1933, de la République de Weimar au Troisième Reich. Klee, dénoncé comme un artiste « dégénéré », démis fin avril de ses fonctions à la Kunstakademie de Düsseldorf, signe un contrat avec Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, le premier et le plus grand des marchands d’art moderne ; puis se résout, fin décembre, à repartir en Suisse.

L’aquarelle n’a connu que trois propriétaires : Lily Klee, la veuve de l’artiste, et sa fondation ; Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler et la galerie Louise Leiris qu’il avait créée ; enfin, Alfred Neven DuMont, magnat rhénan de la presse et de l’édition, propriétaire entre autres du Kölner Stadt-Anzeigen, décédé en 2015.

Ce n’est pas un hasard si ce dernier, grand collectionneur d’art moderne, personnalité proche de tous les chanceliers allemands de l’après-guerre (d’Adenauer à Merkel), éditeur de plusieurs ouvrages sur Klee, avait choisi cette œuvre. Sans doute appréciait-il son graphisme rare, mi-abstrait, mi-figuratif (à la Miró, pourrait-on dire), qu’on ne trouve guère que dans quelques œuvres de 1933. Surtout, en quelques lignes étonnantes de dynamisme, Klee dit, ou plutôt, rend visible sans discours (« l’art ne reproduit pas le visible, il rend visible », avait-il écrit en 1920), ce moment où l’Allemagne bascule.

On devine deux figures dansant sur un rythme, peut-être, de fox-trot. C’est l’Allemagne des années 1920, des films de Pabst dont le meilleur exégète, le critique Siegfried Kracauer, écrivait que « dans les scènes de night-club il suggère le vide de ses personnages par le vide qui les entoure » (De Caligari à Hitler, Princeton, 1947). C’est bien ce qui surprend ici, de prime abord, chez Klee qui procède d'ordinaire par ajouts et nuances jusqu’à emplir l’espace.

Mais est-ce un rythme de fox-trot ou le pas de l’oie, que suggèrent les bottes (et peut-être, une moustache) noires ? Quant aux trois points gris, noir, et brun, ils évoquent une tête, des yeux, un centre nerveux qui se déplace avec les figures, mais aussi les couleurs de l’extrémisme politique et ce « point gris » cher à Klee qui le décrivait dès 1926 comme « le point fatidique entre ce qui devient et ce qui meurt ».

Carl Einstein, le premier théoricien de l’art moderne, estimait que l’art de Klee retrouvait « la même force magique et prophétique » que l’enfance ou les sociétés primitives. « Les titres de Klee », poursuivait-il, « donnent l’impression d’être de vieux noms magiques (...). Ils délimitent de prime abord l’expérience du tableau » (L’Art du XXe siècle, Berlin, 1931). Le titre apposé par Klee lui-même en bas de cette œuvre, Verhext und eilig, mot à mot « Ensorcelé et pressé », ajoute à cette magie inquiète.