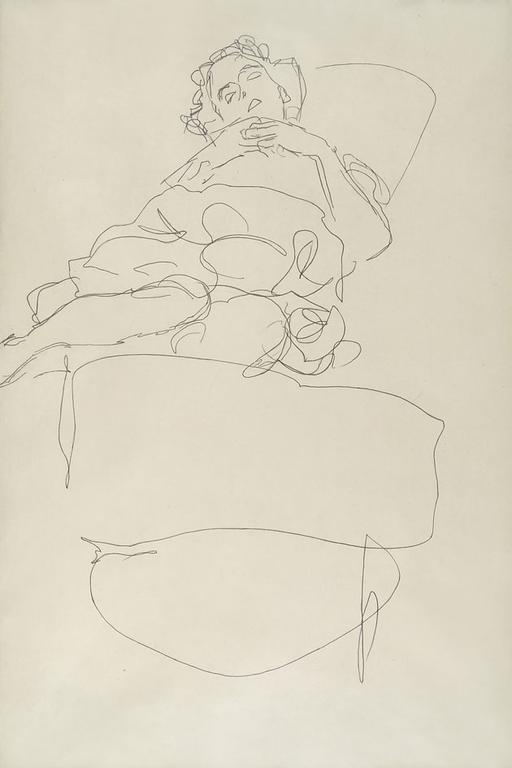

Femme allongée sur un lit

Gustav Klimt (1862 Baumgarten - 1918 Vienne)

1908

Crayon noir sur papier ; 56 x 37,3 cm

Provenance :

Gustav Nebehay (1919) ; New York, collection privée ; Vienne, galerie Bei der Albertina ; Vienne, collection privée ; Paris, galerie Eric Coatalem ; Paris, collection Le Polyptyque ; Paris, collection privée.

Exposition :

Gustav Klimt, dessins (Paris, galerie Eric Coatalem, 2008).

Bibliographie :

Alice Strobl, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, vol. IV, 1984, n° 3660.

D’après Alice Strobl, ce dessin serait une étude préparatoire à l’un des tableaux les plus importants de Gustav Klimt, die Jungfrau (la Vierge), achevé en 1913 (Prague, galerie nationale). Toutefois, la ligne très assurée, virevoltante, rare dans l’œuvre graphique du peintre, ne se retrouve guère que dans quelques dessins autour de 1908-1909.

Klimt a rencontré Egon Schiele en 1907. Dans les années qui suivent, il s’éloigne de l’esthétique de la Sécession et renonce à intégrer l’or dans ses peintures, pour se consacrer surtout au paysage et à quelques grandes peintures allégoriques. Mais s’il influence Schiele, qui n’a pas encore vingt ans, la réciproque est vraie : l’esprit de Schiele semble ici guider le crayon de Klimt.

On peut faire l’hypothèse que Klimt a saisi l’occasion de croquer une amie ou compagne – elles furent nombreuses – dans une attitude d’abandon propre à évoquer ou le sexe ou la mort, sources où puise sa peinture et plus généralement la culture de la Vienne fin de siècle – si l’on admet que le 19ème siècle finit en 1914. Et l’a « transformée » quelques années plus tard en la femme dénudée qui figure dans le bas du groupe, et qu’à vrai dire on ne reconnaît guère qu’à l’inclinaison de la tête.

L’historien d’art Werner Hofmann écrit joliment, dans le catalogue de l’exposition Vienne 1880-1938, L’Apocalypse joyeuse (Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, 1986), que Klimt « ne voit dans l’instinct érotique que l’instigateur des arabesques les plus osées dont le corps humain, seul ou en couple, soit capable ». Plus facilement dans le dessin que dans la peinture, où la ligne est en quelque sorte canalisée par la conception d’ensemble, fluide plutôt que jaillissante.

D’un moment où la disposition du modèle rencontre la disponibilité de l’artiste naît, en quelques traits, un dessin mémorable – quand beaucoup d’autres de Klimt, qu’il faut bien qualifier d’hésitants, presque de fuyants, ne le sont guère. On pense, le compliment n’est pas mince, à Rembrandt, vers 1635, dessinant Saskia endormie (New York, Morgan Library).